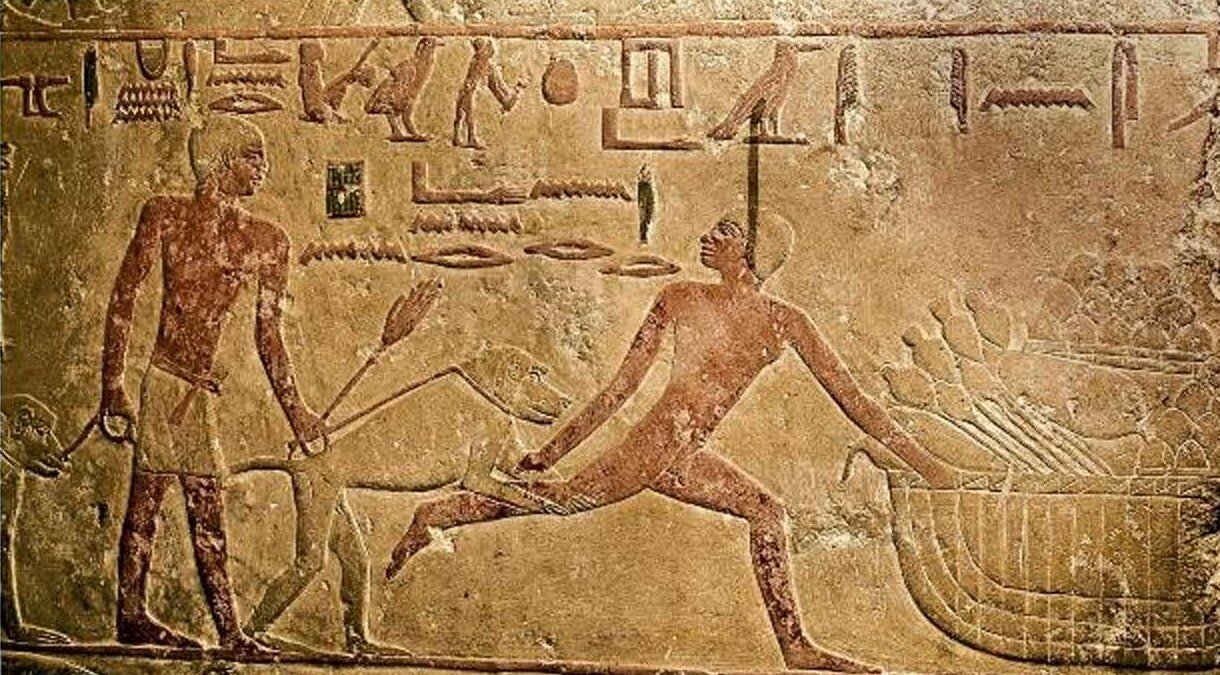

(Old Kingdom, 5th Dynasty, ca. 2498-2345 BC. Detail from the Mastaba of Tepemankh, Saqqara necropolis. Now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 37101)

On the baboon Police:

Hieroglyphs and artwork have survived the ages depicting Egyptian authorities using baboon on leashes to catch criminals, in much the way modern police would use a dog. The most surprising use for trained baboons was as police animals. One shocking bit of classical Egyptian artwork depicts authorities unleashing a baboon on a thief in a marketplace, and the criminal begging them to call the animal off as it bites his leg.

Scenes of daily life on tomb walls recalled the life of the deceased in this world. This part of the low-relief of Tepemankh is an example. A nude man is grasped round the legs by a large baboon. He is trying to keep the baboon away with his left arm. A second man is behind them. He is wearing a short kilt and holding a whip with one hand. On his other hand he leads a female baboon who is carrying a baby. There are still traces of color.

On the veneration and mummification of baboons:

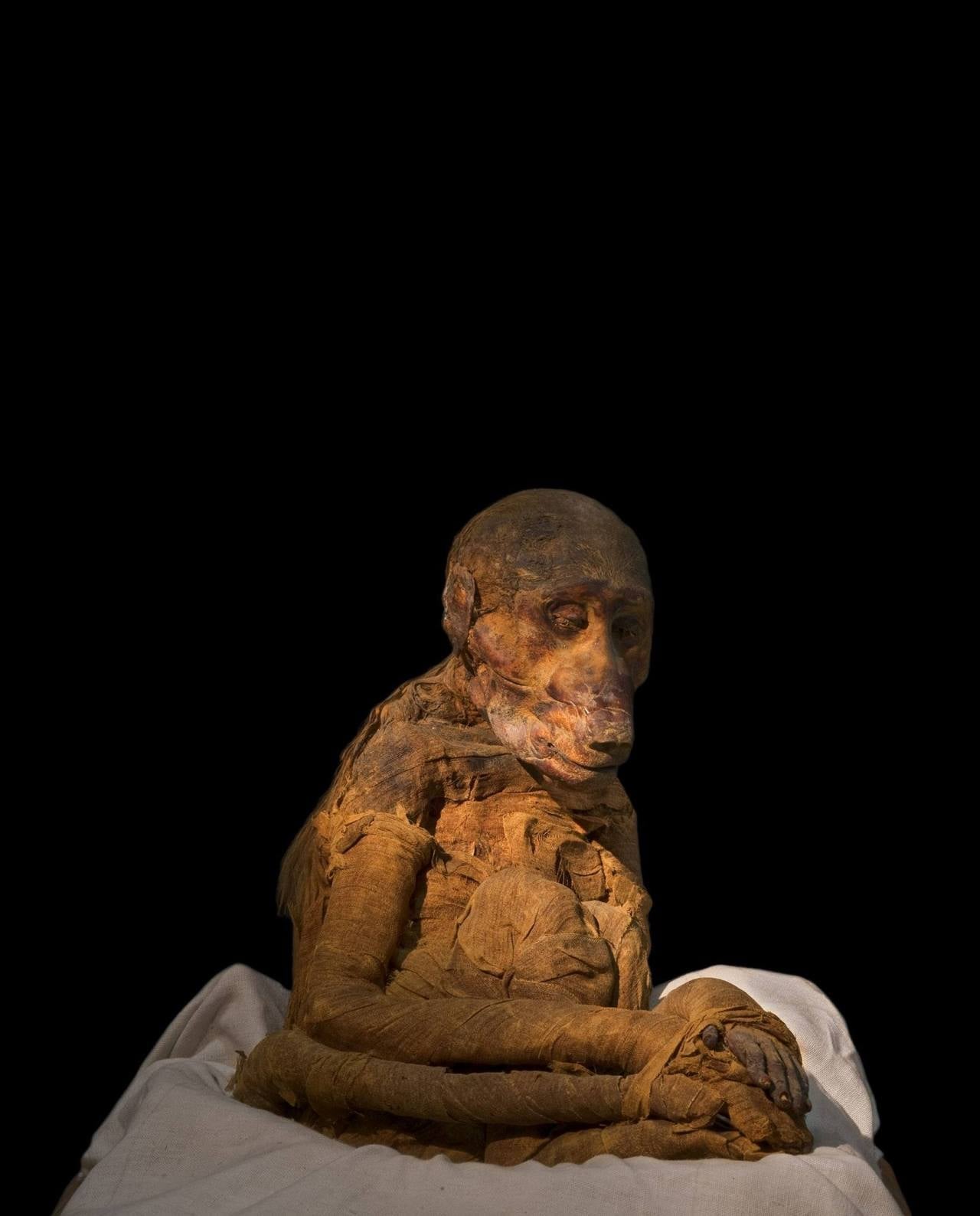

(Excavated by Mr. Theodore M. Davis in 1906 from Tomb (KV51) near the Tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35), Valley of the Kings, West Thebes. Organic remains, linen. Now in the Egyptian Museum.)

This baboon mummy is seated with its knees drawn up to its chest, and its tail curving around the right side of its body. The monkey appears to have been mummified through an enlarged cut in the anal area rather than evisceration through enema; radiographs show that a series of large packets that appear to contain soil were inserted into the animal’s torso to help hold its original shape. Traces of resin, natron, and exterior bandages are still visible on the animal.

Although isolated cases of domestic animals mummified by their masters are known, perhaps to keep them at their side in the afterlife, most animal mummies had a votive function. Pilgrims visiting the temples offered to the deities mummified animals associated with them (Thoth/ibis or baboons, Bastet cats, Anubis/dogs, Sobek/crocodiles, Horus/hawks, etc.). Animal mummies would often be buried in necropolises specifically dedicated to them.

Recently, vast necropolises of mummified animals have been discovered. Tomographic scans offer new opportunities to study the methods used to embalm and preserve these relics, as well as provide important information for forming a map of Egyptian fauna.

In the collections of the British Museum in London, a mummy known simply as EA6736 sits in eternal repose. Recovered from the Temple of Khons in Luxor, Egypt, it dates to the New Kingdom period, from 1550 B.C. to 1069 B.C. Clues to the identity of EA6736 emerge after close inspection. Its painstakingly wrapped linen bandages have disintegrated in some places, revealing fur underneath. Stout toenails poke out from the bandages around the feet. And x-ray imaging has revealed the distinctive skeleton and long-snouted skull of a primate. The mummified creature is Papio hamadryas, the sacred baboon.

EA6736 is just one of many examples of baboons in the art and religion of ancient Egypt. Appearing in scores of paintings, reliefs, statues and jewelry, baboons are a recurring motif across 3,000 years of Egyptian history. A statue of a hamadryas baboon inscribed with King Narmer’s name dates to between 3150 B.C. and 3100 B.C.; Tutankhamun, who ruled from 1332 B.C. to 1323 B.C., had a necklace decorated with baboons shown adoring the sun, and a painting on the western wall of his tomb depicts 12 baboons thought to represent the different hours of the night.

Egyptians venerated the hamadryas baboon as one embodiment of Thoth, god of the moon and of wisdom and adviser to Ra, god of the sun. The baboon is not the only animal they revered in this way. The jackal is associated with Anubis, god of death; the falcon with Horus, god of the sky; the hippopotamus with Taweret, goddess of fertility. Still, the baboon is a very curious choice. For one thing, most people who routinely encounter baboons regard them as dangerous pests. For another, it is the only animal in the Egyptian pantheon that is not native to Egypt.

(Faience figure of Moon God Thoth), 7th – 6th century BCE, Minneapolis Institute of Art.)